David Bentley Hart has emerged as quite the controversialist these last few years, and I suppose it’s time to bring the controversy to the pages of Catholic Bible Talk with a multi-part review of his translation of the New Testament.

In 2016 David Bentley Hart was an Eastern Orthodox academic theologian with a column in First Things and a devoted fan base who loved him for his delightful yet cutting wit—usually applied to dismantling the arguments of the New Atheists, Calvinists, and golf fans. By 2020 he is writing about the apocatastasis in the New York Times, getting into public spats with NT Wright, and getting condemned for heresy by James Martin, SJ. What happened?

Well, he translated the New Testament.

The first hints were in an article he wrote entitled “Christ’s Rabble: The First Christians Were Not Like Us”, published in the September 2016 issue of Commonweal. The article begins,

For two and a half years I have been working on a translation of the New Testament for Yale University Press, which I recently completed. It should not have taken me that long, but an extended spell of ill health disrupted my life just as the project was getting under way. The only good result of this is that the delay forced me to take an even more reflective and deliberate approach to the task than I might otherwise have done; and this, in turn, caused me to absorb certain conclusions about the world of the early church at a deeper level than I could have anticipated. Most of them I already knew, admittedly, if often as little more than shadows glimpsed through a veil of conventional theological habits of thought—for instance, how stark the dualism really is, in Paul’s letters and elsewhere in the New Testament, between “flesh” and “spirit,” or how greatly formulations that seem to imply universal salvation outnumber those that appear to threaten an ultimate damnation for the wicked.

David Bentley Hart — “Christ’s Rabble: The First Christians Were Not Like Us” Commonweal, 27 Sep 2016

When it was published about a year later, it earned press in the usual places that review new biblical translations, but also the Atlantic (where Garry Wills reviewed it), the Los Angeles Review of Books, England’s The Literary Review (which magnificently titled their review “The Unauthorised Version) and other secular publications. Reviews honed in on the strangeness of the translation. Exceedingly literal—Hart called it “pitiliessly literal”—its vocabulary was quite different from that of traditional translations. Where was “hell”? Or “eternity”? Or “righteousness”? Or “justification”?

A bad review by NT Wright in The Christian Century provoked Hart to vent some bile on the Eclectic Orthodoxy blog. In part he criticized Wright for even publishing the review, considering Wright already had his own translation of the New Testament and it was bad form to review competitors. He then rolls up his sleeves and meets the popular retired Anglican Bishop point for point. The broadsides merited a write-up in Christianity Today.

In the fall of 2019, he followed this work with a slim book that he viewed as an epilogue to his entire project of biblical translation: That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation, basically a collection of essays presenting proofs that all will eventually be saved. Far from a broadminded pantheism, as you might reasonably assume, he draws from classical philosophy, the scriptures, and the Church Fathers, chiefly Gregory of Nyssa, Maximus the Confessor, and Origen.

Let me say here that the Catholic Church’s magisterium does not allow us this amount of certainty. The Catechism affirms Hell and its eternity, though the outer limits of the Church’s theology on the subject has been explored in work by some the most important 20th century theologians in works such as Hans urs von Balthasar’s, Dare We Hope that All Men Be Saved? (While that particular book is indeed controversial, it would be less so if people took the trouble of actually reading it.)

David Bentley Hart began writing occasional opinion pieces for the New York Times in the summer of 2019, causing a small fuss with a piece named “Can We Please Relax About Socialism?”, but that was nothing compared to an article where he questioned how one could believe in an eternal Hell. This provoked none other than Father James Martin to describe it as, “a strange piece that neglects Jesus speaking about Hell often and in detail.” The priest then detailed several scripture citations on his Twitter, which provoked a wag going under the handle @WB_BASKERVILLE to label the high profile Jesuit priest, “Fr James ‘Hammer of the Heretics’ Martin, SJ”.

Something about David Bentley Hart makes people lose their minds. It might be his intelligence, but more likely it is his belligerence and comfort in “naming names” and engaging in petty intellectual squabbles that give people pause about him. For others, it is his lack of discretion taking an intramural theological squabble to the opinion page of the New York Times.

One thing you ought to know if you are unfamiliar with the Eastern Orthodox tradition, is that thinkers of Hart’s sort are not unwelcome in their communion. While we Latins have our rich dogmatic tradition, in the Christian East, if it is not in the first seven ecumenical councils or the historic creeds, it can be up for debate. Hart’s progenitor Sergius Bulgakov, the Russian Orthodox theologian active in the 1910s through his death in 1944 was also a strong defender in the apocatastasis who wrote about the eventual salvation of even the unclean spirits. While some aspects of his theology were criticized through official channels, his belief in the apocatastasis was not.

As for the opinion of history that Origen was a heretic, his theology was not condemned until long after his death, the condemnation is now believed to have been maliciously inserted into the canons of an ecumenical council when they had never been discussed at that council, and at any rate it is unclear what the condemnations have to do with Origen’s actual theology as we have it today. It seems likely that it was the work of those who built upon his speculative works who formulated the doctrines that were condemned.

I hope I have conveyed that, whatever emotions this brings up in you, this is a complex topic, but I’ve gone on for too long already. We are here to talk about something else.

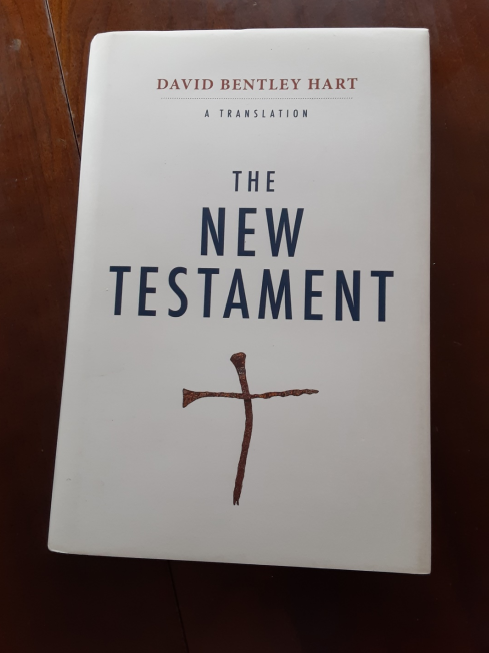

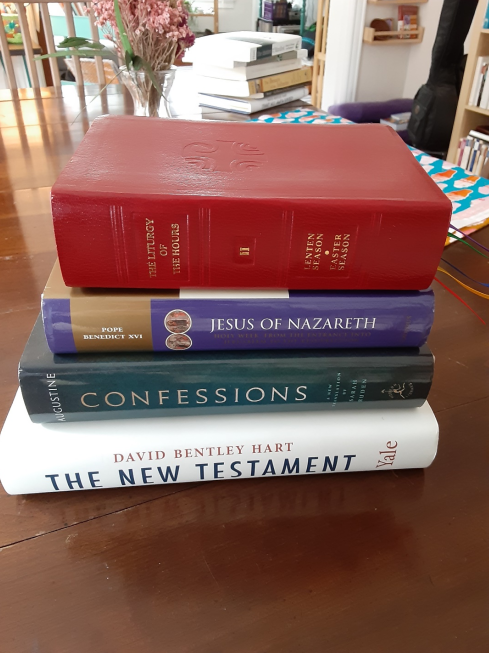

The book itself is what appears to be a sewn hardcover, and a large one at that—over 9 inches high and 6 inches wide. Here it is compared to the recent Ruden translation of Augustine’s Confessions, Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth, and my breviary. Its size makes it a pleasure to hold in the lap, but a pain to read in bed.

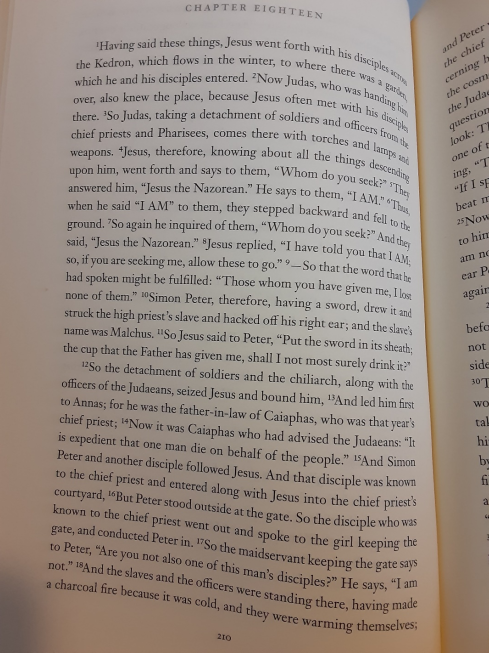

We will continue with some of the preparatory material—of which there is much, but to whet your appetite, here is how his translation does the start of John 18.

Interesting that he uses “I AM” in verse 5 and following. I’d love to see the footnote on that. The NABRE does the same thing, interpreting it as a reference to the divine name. Their “falling back” in verse 6 makes a lot more sense then. I always thought the NAB translation was very bold there, as most translations use “I am he”, lower case and much more prosaic.

I like the NAB here and find it interesting that Hart made the same choice.

Thanks for the review. I think I’ll have to pick up a copy!

Steve

In verse 12 he uses “… and the chiliarch”. Who in the world would know the meaning of that?

Steve,

If I might recommend a certain caution. I have studied this at some length, and even engaged in some online discussion with Hart, and while my conclusions are my own, I do not see how it is possible to place Hart (or Balthasaar, for that matter) within the traditions handed down by the Church.

For that matter, even Hart’s conclusions on his orthodoxy are less sanguine than the reviewer’s…. He rather candidly commented recently:

“First, I am told that some readers believe I am preaching heresy in my book [That All Shall be Saved], even apostasy. I accept without defense that this may well be so, according to many or most understandings of both orthodoxy and Orthodoxy… I probably am heretical on many points. I did say in the introduction to my book that I was attempting a logical and rhetorical “experiment.” Still, for any offense I have given to the faith of anyone, I can plead only good intentions.”

He elsewhere asked for prayers, which I encourage any and all that read my comment to do.

When all that is combined with the fact that “That All Shall Be Saved” is a sort of companion volume/commentary to his translation, a translation that has (of course) no imprimatur from the Church, I would be cautious at best.

Bible collecting is half (maybe more than half) hobby to many of us, myself included, but we only have so much time to devote to the development of our spiritual life. It is important that time not be frustrated straining to go in directions that Holy Mother Church has already foreclosed.

Bob Short,

Great article and a great collection of hyperlinks. Your reference the “spat” between N. T. Wright and David Bentley was very interesting. This app would not let me paste a picture of N. T. Wright’s translation: “The Kingdom New Testament”, of the start of John 18 for purposes of comparison. However, my observation is that Wright’s rendering is more readable; however, overall there is really not much different between the two readings. Oddly, verse 1 demonstrates the literal approach of Bentley versus most translations. I have typed the Bentley and Wright versions of John 18:1 below:

Bentley:

Having said these things, Jesus went forth with his disciples across the Kedron, which flows in winter, to where there was a garden, which he and his disciples entered.

N.T. Wright:

With these words, Jesus went out with his disciples across the Kidron Valley to a place where there was a garden. He and his disciples went in.

Note the omission of “flows in winter” in Wright’s edition. In the Greek there is a word “cheimarrou” which in some interlinear versions is translated as “winter gush” or “winter torrent.” Almost all translations simply ignore this word as did Wright .(see RSV, ESV, NRSV, NIV.) An exception to this is omission is the NABRE which has a note: “Kidron valley: literally, “the winter-flowing Kidron”; this wadi has water only during the winter rains.”

Does the omission of “flows in winter” change our theological understanding of the Chapter? No. However, since it is clearly in the original it should be included in the translation or noted, as in the NABRE, that it is missing.

The hyperlinks were from Marc to save you all time on hunting down these squabbles!

I am not a Greek scholar, so forgive me if I go wrong here, but while the etymology of the constituent parts of the word is something like “winter + flow”, I understand the meaning to be less specifically seasonal and more generally a “torrent” (which is how the Confraternity translates it, FWIW).

These sorts of things give me pause, because pulling apart words into their parts only works some of the time, otherwise it can be like saying “Grandfather” means “a dad that is a really big”.

He actually writes about this at length in his book of essays “Theological Territories”. I got it because about 25% of it is after the fact commentary on some of his out-of-left field renderings in his translation, and I was curious what he said about it. My understanding is that his rendering was influenced by the Septuagint’s use of the word, which was not used to for the Hebrew equivalent of “stream” but the Hebrew equivalent of “wadi”. (He points to a part of Job where the word describes an explicitly dry stream bed. The translation was also influenced by the fact that the Kedron is still there, and is dry most of the year.

Some of the dictionaries I looked at listed “arroyo” as one of the meanings, which is in keeping with that. Not that I am advocating for “arroyo” by any means… 🙂

First as I said above, while theologically unimportant, ignoring the word “cheimarrou” in Wright’s Bible and nearly all modern translations without noting the omission as done in the NABRE is “wrong.” I would suggest that while the Confraternity, Douay-Rheims and Vulgate don’t ignore the word they got it wrong with using a word for word translation in using the word “torrent.” John is telling us that the river bed is dry as it is spring time and the river flows only in the winter. Why? Perhaps, during the winter rainy season, going from Jerusalem to the Garden when the river is high, the trip to the Garden may have been a long one, if even possible. Hence “torrent” by itself has no seasonality and implies that there was a fast moving stream, and is probably not a good translation of “cheimarrou.” If I had to pick a one word translation probably the words “wadi” (a word from the Arabic) or “wash” would be better. Again, there is nothing theological going on here so I kind of apologize for extending this thread and it is OK to not publish it.

A few things should be noted.

1) Most Orthodox are not universalists. But there is debate about whether the Fifth Ecumenical Council actually condemned universalism at all or at least only condemned it in a particular form. The debate centers on whether the anathemas against Origen were originally part of the council or was part of a local synod attached to the council at a later date. Some argue even if those anathemas were original, they only target a very particular form of universalism that developed long after Origen’s death.

2) Universalism in Orthodoxy is usually based on the premise that there is a hell but it is not eternal and that is that is possibility of conversion post-mortem. Fr. Stephen De Young (an Orthodox Bible Scholar), who is NOT a universalist, advocates this view of post-mortem conversion based on his own reading of Second Temple Judaism and early Christian texts. See https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2019/12/01/the-antiquity-of-hell/

Fr. De Young also comments on the Hart NT translation in a balanced way here. https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxyandheterodoxy/2018/05/08/david-bentley-harts-the-new-testament-a-review/

3) Post schism councils considered to be ecumenical by the Catholic Church have stated pretty clearly that no post-mortem repentance is possible, Lyons, Florence, and Trent among them. So it appears that Balthasar’s hope depends on the conversion before death.

On my to read list is a book called “Decreation: The Last Things of All Creatures” by Paul Griffiths. Among his goals is provide a justification of universalism that is within the bounds of Catholic Magisterial Teaching. Since I haven’t read it yet, I can’t comment on how well it succeeds (or fails).

Thanks for mentioning Paul Griffiths’ book, Devin. That looks fascinating. I added it to my Amazon list.

Paul Griffiths is an interesting interlocutor, and as pugnacious as David Hart. I also have had this, and several other, of his books on my wish list for a while. I would be interested to hear any thoughts on it.

Re: Balthasar.

It might appear that, but not really. Balthasar certainly seems to appeal to at least to the possibility of a post-death conversion. While he dances around straight out saying that–as he dances around straight out saying anything, it seems the logical conclusion of his speculations of a damned soul literally meeting Christ in Hell and being converted by the meeting.

No less theologian and major Balthasar-scholar than Fr Edward Oakes of Mundelein Seminary referred to that as his “trump card.”

That this is a proposition explicitly rejected by the Church a false does not seem to have troubled Balthasar much in speculating that it might nevertheless be true…

It is worth noting here a kind of similarity in approach for Balthasar and Hart, though their argumentation and theology is quite different. In approach, both were quite certain that had struck on a truths that tradition had overlooked; at least neglected and possibly rejected, and that this persecuted or forgotten truths needed to be restored and the tradition corrected.

(In Balthasar’s case this list is quite extensive, dealing with the life of the Trinity, Incarnation, Christology, soteriology, the Descent, Scripture, etc., etc.)

Another is a willingness to re-interpret Scripture and Tradition along pre-commitments at odds with the witness of Scripture and Tradition. To quote one scholar on that point, “[Balthasar’s] theology determines the meaning of Scripture, not the other way around.” Hart is similar here, commenting that if it could be demonstrated that Christianity required a belief in Hell, he would refuse to be a Christian.

I could go on at some length on this. But instead I would recommend reading Fr Oakes and Alyssa Pitstick’s correspondence in First Things, as well as her book Light in Darkness which is necessary reading, as well as Card. Avery Dulles commentary, I forget the name, but also in First Things. Fr Thomas Joseph White’s article on Balthasar and Journet and the Twofold Will of God, Fr Schenk’s article on the Epoche of Factical Damnation, Ralph Martin’s paper on Balthasar and Salvation, Fr Scanlon’s on Balthsar’s Reputation, and the great, old scholarly work by the Anglican Divine, Edward Pusey, “What is of Faith as to Everlasting Punishment?”

That is a kind of highlights version, but it is a good start. Some of those are specifically about Balthasar, but Pusey’s writings are equally in dialogue with Hart (if 100 years older).

Though Hart mocks them roundly, I think that the Protestant historian Michael McClymond’s reviews of That All Shall be Saved (in First Things and elsewhere) are worth a read. One is called the Opiate of the Theologians, IIRC.

Well, you have listed the majority of critical treatments of Balthasar’s work published in English. I think the only one you forgot was Karen Kilby’s book.

Fr. Edward Oakes, SJ’s book Pattern of Redemption is a good, balanced introduction to Balthasar’s thought. He is not a Balthasar fanboy in the least and you will have a holistic view of his theology that you won’t get from Scanlon or Dulles, for example. Even better though, but far more taxing would be to read one or more of Aidan Nichols, OP’s books on Balthasar. Aidan Nichols is no sentimental liberal. Far from it. Neither is Balthasar, as anyone who has read “Short Primer for the Unsettled Layman”, “Who is a Christian?”, and “The Moment of Christian Witness” (or frankly any of his work) could tell you.

While “Dare We Hope…” has a reputation as a universalist text, its a book Hart hates because it is not a universalist text. It contains some of the most clear eyed and sobering reflection on what eternal separation from God means that I have ever read. (I haven’t read Eschatology by Benedict XVI–when he was still Joseph Ratzinger–yet, but I plan to fix that soon.)

The Stations of the Cross that Balthasar wrote were used by Pope John Paul II. The same Pope named Balthasar a Cardinal, but he died before he arrived in Rome to receive the red. He founded the journal Communio with de Lubac and Ratzinger, an action that had a tremendous influence in correcting the overzealous and worldly interpretation of Vatican II prevalent at the time in theology. He co-wrote a book with Cardinal Ratzinger on Mary. In a speech later published by Ignatius press in “Introduction to the Catechism of the Catholic Church”, Cardinal Schonborn spoke about currents in theology too new to find their way into the Catechism that would need to be meditated upon and digested by the universal Church–and the example he chose was Balthasar’s theology of Holy Saturday.

This is not to say that Benedict XVI and de Lubac signed off on each flight of fancy in Balthasar’s work. Someone has claimed Benedict expressed reservations about Mysterium Paschale in a private conversations but I have yet to see a quote by him on the subject. That being said, I think its far off the mark to dismiss Balthasar on this subject any more than one should dismiss Gregory of Nyssa for his universalism, Augustine for his late proto-Calvinist work, or Thomas of Aquinas for denying the Immaculate Conception. Theology is messy business, it seems. Balthasar’s material is on the conservative end of the Nouvelle Theologie types. He echoes and magnifies many of the criticisms of the Church of the 70s and 80s that you find in Cardinal Ratzinger’s work of that era.

I think Pitstick’s criticisms are quite valid and well presented, but I can’t say I feel the same about Ralph Martin’s work on Balthasar, which I find to be a bit like a hit piece dressed in academic clothes. I know he is coming from the right place: he thinks that presumption about the merciful nature of judgment leads to Christian laxity and lack of evangelical fervor.

Fr. Oakes critiqued Martin’s understanding of Balthasar’s theology in what I understand is a mostly positive review of Martin’s book on salvation.

(As a side note, Don’t let anything I say in this series be confused for endorsement of Hart’s “That All Shall be Saved” or universalism.)

I don’t necessarily agree with Fr Oakes’ critique of Martin’s chapter on Balthasar, but for what it’s worth, I was actually referring to Martin’s more recent _paper_ on Balthasar. It is highly critical of both Balthasar and von Speyr, but given Balthasar’s own identification of his theology with her mysticism the two, in large part, are bound together and the oddity of their relationship is something usually politely skipped over.

As practically troublesome as the “Dare We Hope…” theology might be in itself, that is not really what I find most troublesome in Balthasar’s theology, it is really towards the bottom of the pile. His Trinitarian theology, Christology, and theology of Descent, are all much, much more disturbing and much further afield from Tradition.

In some ways, arguing over what Balthasar precisely means in “Dare We Hope” has served to deflect critical attention away from his broader theology, even though “Dare We Hope” is really just its logical end.

Because of his departures in those fundamental areas, I don’t think HvB is in the least conservative, since he pays little debt to Tradition. That doesn’t make him a “liberal”, but not being Hans Kung is not the same thing as being a conservative. However, after V2, not being Hans Kung was about all it took to be grouped with conservatives, and I think that is more or less what has happened (not that either de Lubac or Ratzinger were that conservative back then either).

Short version, I am with Karl Rahner (not exactly a conservative either) about HvB, that he “conceptualizes a theology… that appears to me to be a rather gnostic position.”

To press Fr Rahner’s point in a direction he probably did not intend, this gnostic flavor is also present in the sheer _creativity_ of Balthasar’s conceptions as he describes ur-kensosis, the “distance” between the persons of the Trinity, the “stretching” of Christ’s human nature, the Son’s abandonment in Hell, etc., etc., all sorts of suppositions unknown to Scripture and Tradition, in much the same impossible, yet matter-of-fact detail of Valentinus describing the inter-relationships among the gods in the pleroma.

To that, I’ll borrow for the the dismissively humorous reply of St Irenaeus: “Along with this Cucumber exists a power of the same essence, which again I call a Melon. These powers, the Gourd, Utter-Emptiness, the Cucumber, and the Melon, brought forth the remaining multitude of the delirious melons of [Balthasar].”

I don’t want this discussion on Balthasar to go on and on, but I disagree that his suppositions are unknown to Scripture and Tradition.

The figure of Adrienne von Speyr is certainly the crux of Balthasar’s theology. He made no secret of the mystic’s influence. The fact that some question the relationship between Balthasar and Speyr in a way that we don’t question Francis de Sales and Jeanne Chantal or Fr. Colombiere and Margaret Mary Alacoque seems to me more a comment on our gossipy and voyeuristic age than on Balthasar and Speyr.

Speyr is an odd one. We know more about Speyr than most mystics of her sort because she had Balthasar as a spiritual director who devoted hours each day to taking dictations from her and wrote a biography. I am not an expert in her work, but it seems that any novelties in Balthasar’s theology are from her work.

A major part of his theological project was to integrate mysticism and theology in a way they hadn’t been integrated in the West since Scholasticism. The ressourcement theologians were all trying to return to the patristic method of theology in their own ways and Balthasar went the furthest in that regard, considering he was the spiritual director of a stigmatist visionary and wrote with the same freedom as the Church Fathers.

The people who look over causes for canonization are doing their slow work on Adrienne von Speyr. Considering the mass of writing Balthasar transcribed, it will take them a long time.

I don’t think there is any comparison between Valentinus’s speculation and Balthasar’s Trinitarian theology. What ground for comparison is there? That they are both gnostics? I think Rahner (who had no qualms about sending students to Balthasar) was using the word as an adjective and not a label. Is it because Balthasar pulls his material about the Trinity out of thin air, as it were? In what way does he? The New Testament presents Jesus as emptying Himself, as showing obedience to the Father. His theology on the Trinity is not very arcane, but is an attempt to integrate this biblical data into the developed concept of the Trinity and the relationship between these persons.

And what is tradition? Is it only Thomism? Balthasar spends a lot of pages interacting with theologians who came before him, and I see far more engagement with the biblical text than I do in many other theologians.

Balthasarians (to invent a word) seem more likely to be theologically conservative these days: cf. the use of his theology of marriage in the Synods of the Family in 2014/2015, also Aidan Nichol’s criticism of the Pope last year. (I know I brought the liberal/conservative dichotomy in this conversation, but I am dubious about its worth in discussions of Church stuff).

Anyway, I hope I don’t seem combative, Thomas. Having this conversations in writing and in public is very odd. I feel very strongly that Balthasar is well within orthodoxy and has a lot to say to the Church, especially when read in concert with de Lubac and Ratzinger/Benedict XVI but his opinions, even many that I find insightful and exciting, are small in comparison to scripture, liturgy, and the catechism.

I am curious, and only asking because you are obviously well read: what theologian/school of theology do you think has the most to say to the Church?

“We don’t question Francis de Sales and Jeanne Chantal… comment on our gossipy and voyeuristic age than on Balthasar and Speyr”

Let me clarify “relationship,” I did not mean to imply a romantic relationship. I have never heard or read any suggestions of anything of that sort. What I call odd is precisely their spiritual relationship. He writes in various places that he never made a major decision without her input. That he left the Jesuits (her idea) and moved in with her and her husband to found an institute and dedicate the rest of his life to studying her and writing about her, which he does in hagiographic terms, and accepts even her most fantastic mystical experiences with an infeasible gormlessness. When she berates him for not defending her actively enough from criticism, he treats it as a divine reprimand and repents. This is an exceedingly bizarre–I would go so far as to say, improper–relationship between a spiritual director and the one he is directing, far more ready for comparison to Mme Guyon and Francois Fenelon than to St Francis de Sales and St, Jane de Chantal.

“I don’t think there is any comparison between Valentinus’s speculation and Balthasar’s Trinitarian theology.”

Let me clarify, because Rahner and I were saying different things. Rahner was being more literal, as he was critiquing Balthasar’s introduction of “distance” and a kind of tension within the inner life of the Trinity, leading to the torture of the Son in Hell. As he finishes, “To put it quite crudely; ‘If I want to escape from my filth, mess and despair, it doesn’t help me one bit if, to put it bluntly, God is in the same mess.”

So his criticism is more exact than mine was; he is really saying that Balthasar’s introduction of a kind of interpersonal drama into the Trinity smacks of gnosticism.

I was saying something quite different. I was saying Balthasar’s swaggerinly confident descriptions of the inner life of the Trinity, and the experience of Christ in the Descent,. reminded me of the swaggeringly confident descriptions of the pleroma by Valentinus, because they were both asserting what they could not possibly know.

Thank you for the reference to Kilby, I read Luke Timothy Johnson’s (a theologian I very much respect) review of her book on Commonweal after your post. It is called “God’s Eye View” and I mention it here because it very much captures what I mean.

“Balthasar pulls his material about the Trinity out of thin air, as it were? In what way does he? The New Testament presents Jesus as emptying Himself, as showing obedience to the Father.”

Yes, I do mean that (where “thin air” is roughly synonymous with “von Speyr”). As an example, I wasn’t talking about the kenosis of Christ, I was referencing Balthasar’s strange notion of “Urkenosis”, the kenosis of the Father emptying himself in the begatting of the Son. I will take two quotes from Balthasar here, and simply challenge anyone to find a way to ground them in Sacred Tradition or Scripture:

“God the Father can give his divinity away… [and] this implies such an incomprehensible and unique ‘separation’ of God from himself that it includes and grounds every other separation—be it never so dark and bitter.”

Here is another:

“It is possible to say, with Bulgakov, that the Father’s self-utterance in the generation of the Son is an initial ‘kenosis’ within the Godhead that underpins all subsequent ‘kenosis’. For the Father strips himself, without remainder, of his Godhead and hands it over to the Son… this divine act that brings forth the Son… involves the positing of an absolute, infinite ‘distance’ that can contain and embrace all the other distances that are possible within the world of finitude, including the distance of sin.”

I want to remind that here Balthasar is talking of the inner life of the Trinity from eternity. This is critically important because the ultimate overcoming or traversing of this “distance” by the Son’s absolute obedience is integral to Balthasar’s entire notion of how salvation “works”, and the Cross is something like the eruption into time and space of an eternal alienation between Father and Son in the Godhead produced from the Father’s Urkenosis.

This is obviously outside Scripture or Sacred Tradition, and we haven’t even gotten to his theology of the Descent, where the Son in his Divine Nature is tortured by the Father, that Our Lord lacks the Beatific Vision and has instead a “visio mortis”, that in his utter forsakenness in Hell he does not even know if he will be abandoned and tormented forever…

Alongside all the manifest doctrinal objections to be made, to Balthasar I would level another question, since one could search a thousand years and never find a scrap of any of this in Scripture of Tradition, just how do you know all of this?

“And what is tradition? Is it only Thomism?”

No, it is the whole of what has been always and everywhere taught and handed down; but this has little resemblance to Balthasar.

I would also argue that it is not right to approach this as if Aquinas were pitted against the Fathers, and one must choose which course to follow. Thomas is steeped in the Fathers, and the teaching of the Fathers is consonant with the teaching of Aquinas. And the teaching of Aquinas is consonant with the teaching of the Little Flower, though she knows little of Scholasticism.

But Balthasar goes his own way.

“What theologian/school of theology do you think has the most to say to the Church?”

I hope it isn’t overly broad simply to point to the Doctors as a whole. I think most of them would be surprised if they were thought of as occupying competing schools, since they were all teaching the same Christ from the same Deposit of Faith. Sort of pick any Doctor, and there are great riches. I have a certain fondness for the Eastern Doctors, but that’s just me. As regards the Angelic Doctor, I would hope there would be a renewed interest and appreciation of his deep spiritual, mystical, and Biblical theology. For an example of this, I would point to the truly beautiful book “Aquinas at Prayer” by Fr Paul Murray.

The back and forth on Balthazar was extremely helpful for me. Particular thanks to ThomasL for pointing me to the article by Thomas Joseph White who has become something of my lodestar recently. Was not aware of this article.