Released in 2021, the New Revised Standard Edition Updated Edition (NRSVUE) incorporated more than 20,000 changes to the NRSV text. While currently available through only a handful of publishers, most notably Zondervan and Hendrickson, thankfully our friends at Cambridge University Press are beginning to roll out their own editions of the NRSVUE. Look for Cambridge, in 2024, to publish their full versions of the NRSVUE, hopefully with the same quality as found in their earlier NRSV Reference Bible w/Apocrypha, ESV Diadem, and the ESVCE Cornerstone. Until then, Cambridge has happily released a handy standalone edition of the NRSVUE Apocrypha.

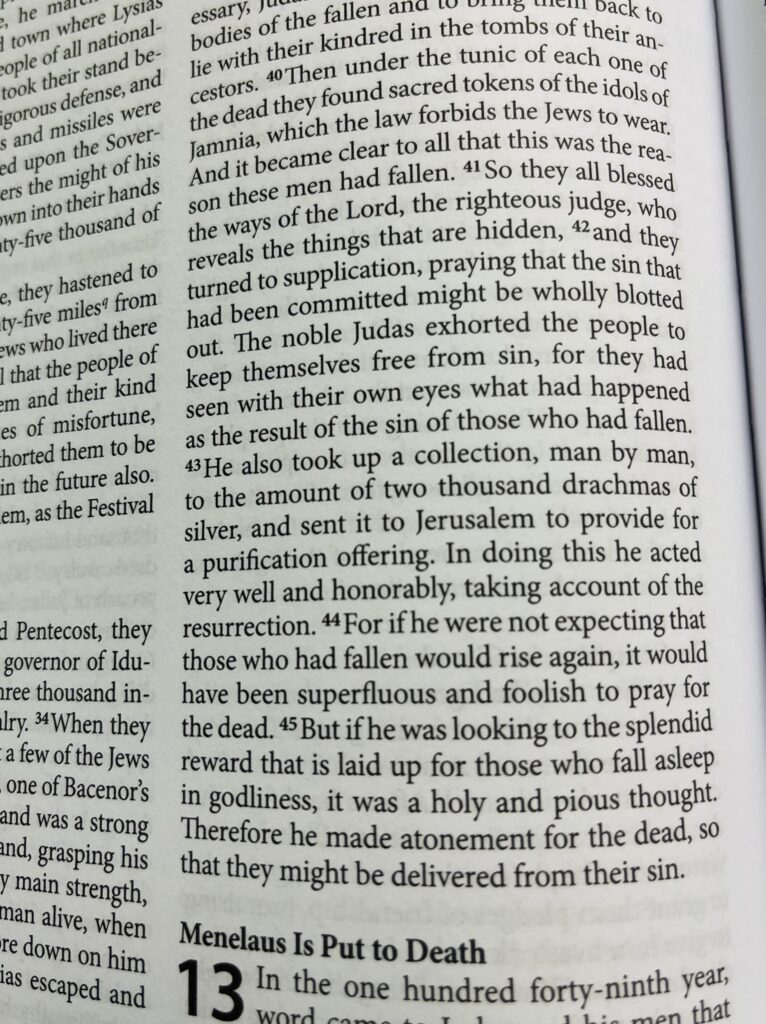

This collection of the Apocrypha contains the full Catholic Deuterocanonical canon along with 1 Esdras, The Prayer of Manasseh, Psalm 151, 3 Maccabees, 2 Esdras, and 4 Maccabees. They are arranged according to four groupings based on ecclesiastical canon. Complete with a “Preface to the Apocrypha/Deuterocanonical Books of the NRSV Updated Edition” prepared by the Society of Biblical Literature, this slim volume presents a readable text that provides the reader an opportunity to encounter both the inherent complexities of translating the Apocrypha/Deuterocanonical Books as well as the style and translation choices specific to the NRSVUE. As the Preface states: “The NRSVue includes a considerable number of changes to the Apocrypha. Because there is no single critical edition of the books in this collection, the team made use of a number of texts (vii).” The Alfred Rahlfs Septuagint (LXX), completed in 1935, remains the base for much of this translation, but other Greek texts as well as the Qumran (DSS) manuscripts are used and noted in the textual notes.

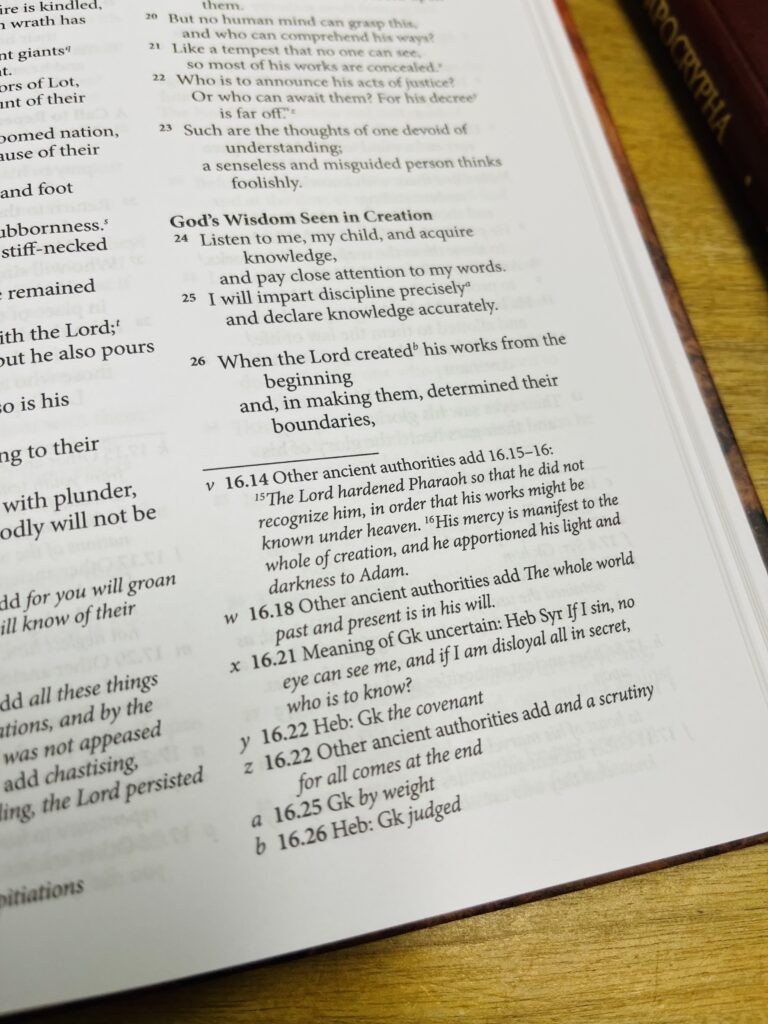

For those specific Catholic Deuterocanonical texts, the Preface explains that the book of Tobit is translated from the “longer Greek tradition (preserved in the Codex Sinaiticus), while taking the Qumran manuscripts and other ancient witnesses into account (vii).” The three additions of Daniel come from the Theodotion. The full Greek LXX version of Esther is provided, following Robert Hanharts 1983 edition. Sirach, also known by various other titles including Ecclesiasticus, has “an especially challenging textual history (vii).” The Preface goes on to note that while they follow the Greek text of Joseph Ziegler, the Qumran and Syriac versions played an important role in the NRSVUE translation. Sirach is the perfect example as to why it is essential to have an edition like this around in order to do more in-depth analysis of these texts. There are a number of pages in Sirach which contain upwards of ten or more textual notes showing you the differences between the Greek and Hebrew versions. With the greater availability of various textual traditions concerning these books, a volume like this is invaluable.

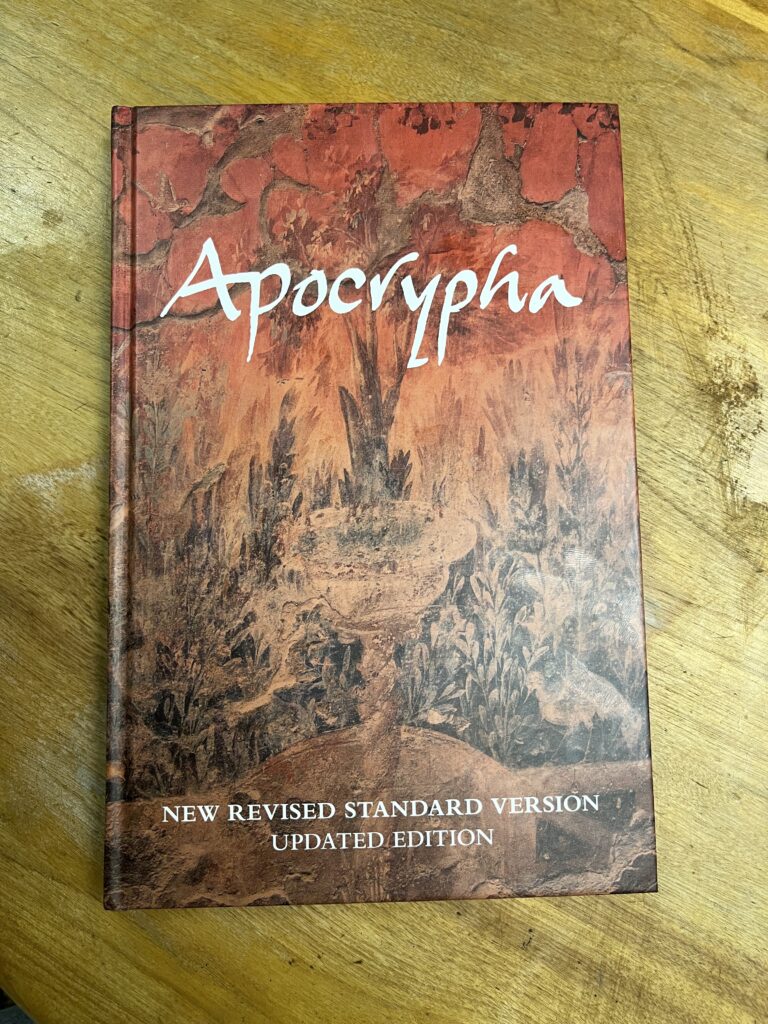

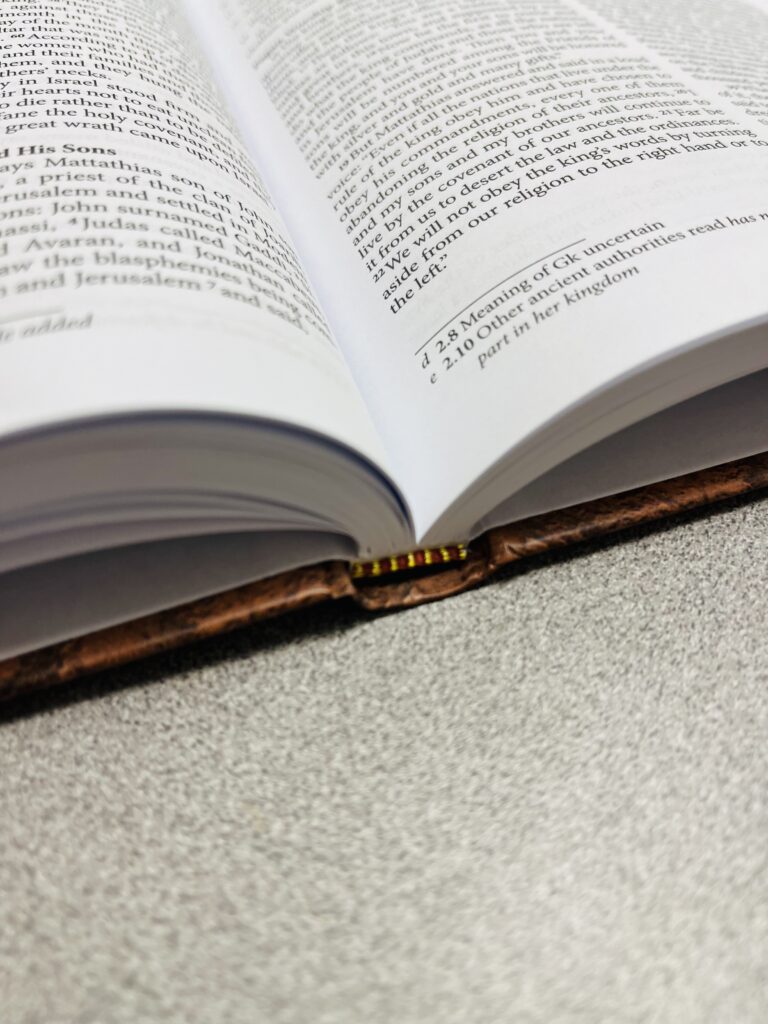

In addition to the usefulness of this edition, the volume itself is pleasing to read and easy to take with you. This sewn hardcover has a beautifully designed smooth cover. The image on the cover is taken from the walls of a home in ancient Herculaneum, preserved thanks to the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD. The pages (248 in total) are printed on thick, white paper that is line-matched. All together, you have a volume which minimizes any issues of ghosting. Typesetting is by Scribe Inc. in a 9.5/10.5 Minion Pro font. The book is printed and bound in Italy by L.E.G.O. (Vincenza).

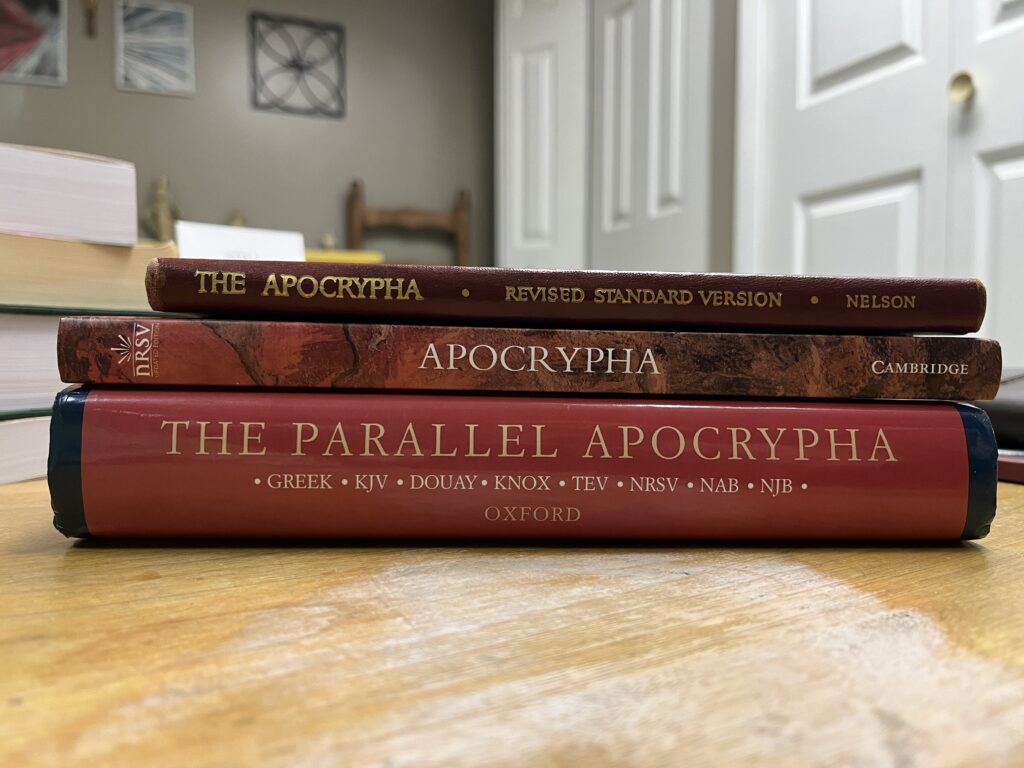

I am confident this volume would appeal to two groups of people. The first group would consist of those who are interested in analyzing the complexities of translating the Apocrypha/Deuterocanonical books and the various textual issues that surround it. The second group would be those who are not completely sold on the NRSVUE translation, but would like to have a physical text to read through before committing to getting a higher-end edition sometime in 2024. If you fall into either of these camps, I would encourage you to consider picking up the NRSVUE Apocrypha from Cambridge University Press. It is a lovely volume and one that I will be keeping close to my other bible study materials for 2024. The NRSVUE Apocrypha comes in hardback and externally looks very similar to the original NRSV Apocrypha from Cambridge, but it is slightly larger, with a new typeface. Having seen the previous version, I much prefer the layout of this new one. The NRSVUE Apocrypha is available now at a retail price of £15.99/ $23.99.

I want to thank Cambridge University Press for providing me with a copy of the NRSVUE Apocrypha in exchange for an honest review.

If you are interested to know a particular verse or two from the NRSVU@ Apocrypha/Deuterocanonicals, feel free to ask in the comments.

Excellent review!

Very good review. However I think I’ll be fine sticking with the NRSVCE and ESVCE until the Augustine CSV gets published in a couple of years, and the new NAB before that. I just don’t trust the NRSVue. And not just me, but professors of mine don’t trust it either.

Mark,

I agree with you regarding the very good review by Timothy. I am curious as to the source of the distrust in the NRSVue edition. Is this distrust simply the same as the NRSV un-updated version, or is it something new?

[Disheveled Willem Defoe enters, gun raised into the air]

“There was a translation fight!!!”

One of my professors was quite blunt, comparing it to the Passion Translation. If you know the backstory to that version, you’ll know that’s not a compliment. Another said it had “hijacked” the authorial intent and cultural context of the biblical authors and jettisoned them in favor of projecting “modern concerns” over the biblical text, presenting the result as a “translation.” And no, both professors said, while they preferred to just use the Biblia Hebraica and Nestle-Aland original language texts, and the NASB for English when needed, they had no real issue with the original NRSV, both calling it a fine translation. They were both of the opinion that any honest biblical or Ancient Near East scholar should just ignore the NRSVue and act like it doesn’t exist. They’re both SBL members, so I’ll bet they’re not fans of the new SBL Study Bible either.

I would be interested to see examples of what they don’t like in the NRSVue. I’ve used it quite frequently for general Bible reading over the past year, and I haven’t found it to be jarringly different from the NRSV. I appreciate some of the updates. Just one example is the translation “faith of Christ” rather than “faith in Christ” in Romans 3:22 and similar passages. To my mind, that is a nice middle ground between the two common schools of thought on how “pistis Christou” should be translated.

I did a verse-by-verse comparison of the NRSVue, RSV-CE, and ESV-CE in several chapters of 1 Corinthians back in July, and the NRSVue seemed well within the lines of reasonable translations there. The one glaring issue was its translation of 1 Cor 6:10, which uses a vague circumlocution rather than explicitly listing homosexuality in Paul’s list of vices. That is certainly worth noting. Other than that verse, I can’t think of anything that struck me as a major glaring problem.

If a person subscribes to American mainline liberal theology (not Catholic Theology) they won’t see a difference. For others, the changes are made to appeal to modern day political sensibilities at the expense of the author’s intent.

Other papers have reported on the word games the scholars have played, in service of their political angedas.

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/nrsv-compromise-homosexuality/

And lesser but still silly examples abound, like changing “Leper” to “man with skin disease”

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Mark+1%3A40&version=NABRE;NRSVUE

The authors back then had no hang-up over labeling people to fit the message of God, but today’s audience seem to need a lot of sugercoating.

I share the concern expressed in your first link about 1 Corinthians 6:9 (and 1 Tim 1:10), but I would argue it isn’t a reason to throw away the NRSVue in its entirety. As the first link points out, the NRSVue has clear language condemning homosexual acts in other verses, so this was not a blanket attempt by translators to remove all moral judgments about homosexuality. It was rather an attempt to find a vague middle-ground to translate a particular Greek word whose precise meaning scholars are arguing about. Now, I think the first link makes a compelling case for why the meaning should not be in doubt, but as Catholics, our faith does not rest on the meaning of individual verses the same way it would for someone who holds to Sola Scriptura. Our faith rests on scripture and tradition, not scripture alone.

To my mind, the second link is merely a difference in language usage. I don’t see a significant theological problem with referring to a “man with a skin disease” rather than a “leper”, and to be honest, I think it corresponds better to the way English is spoken. Outside of the Bible, I don’t think most English speakers would refer to a paralyzed person as a “paralytic” or a person with leprosy as a “leper.” One could argue that these changes in English usage are politically motivated and shouldn’t be imported into scripture translations, but I honestly don’t see the theological significance of such differences. If anything, I think Jesus’ teaching in Luke 13:1-5 and his practice of healing and associating with people who were disapproved by the public opinion would argue in favor of seeing every person as possessing dignity, regardless of their physical ailments or condition.

Why? Because the 1989 text is bad enough, but there can be no question that the 20,000 changes push the text even further in the same direction, and the complete lack of transparency about what was changed, as if they are trying to hide something, should raise the suspicions of everyone. The only way to figure out what exactly what was changed is to go over both texts with a fine toothed comb comparing word by word, and that would take months if not years.

Technically, one could go to BibleGateway, click the option to remove all the footnotes and whatnot, copy the NRSV-CE text for a book into one document since the NRSV-CE matches the text of the ’89 NRSV, copy the NRSVue text for that book into another document, and then use one of those text comparison web tools to highlight all the differences. And then you could scroll down and pluck out the biggest changes while ignoring all the unchanged spots. If someone has something like Logos, it’d probably be even easier to do. You’re right that it’d still be a long slog, but it wouldn’t be like you’d need to examine every verse just to find the changes with the naked eye.

In this blog, we repeatedly see broad generalizations about Bible translations; such that the writer would imply that they would throw most translations in the trash; except their current favorite. Really? Why not take the view, that because of the impossibility of mapping a very small ancient vocabulary into a very large modern English vocabulary, that translators must make judgments regarding the choice of words and sentences. Thus, all translations are, to a degree commentaries. Would you limit yourself to using one commentary? If the answer is no, then why would you limit yourself to one Bible. My suggestion when approaching a new or revised translation is to take a look at how it handles what to you is an especially difficult or especially deep part of the Bible. For example, to me the deepest part of Paul’s writings is Romans 8. As an exercise, I went to Romans 8, and I quickly “eyeballed” the NRSV and the NRSVue and found a difference in Romans 8:10.

NRSV: “But if Christ is in you, though the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness.”

NRSVue: “But if Christ is in you, then the body is dead because of sin, but the Spirit is life because of righteousness.”

In my view these two translations are not quite in agreement regarding their meaning. Pursuing the differences would be a wonderful half hour in a Bible Study. One could also expand a study of this verse in how other translations approach the Greek word “pneuma.” That is as Spirit or as spirit. Lastly, regarding Romans 8:10, in my opinion, if you look at a Greek Interlinear resource, the NRSVue is closer to the literal Greek than the NRSV.

In summary, let us not slam a whole Bible translation on broad generalities as you will be throwing away a valuable resource. Rather, at times go deeper into apparent differences and see what they mean. I think you will find that effort will result in a deeper understanding of the word of God which; in turn, will stimulate your intellectual curiosity.