At least since the Second Vatican Council, the Church has invited the whole flock return to the ancient and medieval practice of praying with Scripture. Since then, Lectio Divina has been big business—at least as far as Catholic publishing goes. Books on the subject have been published by everyone from monks to apologists. Beyond that there are pamphlets, parish workshops, and video series to help people add another tool into their spiritual toolbox.

On one level, more lay Catholics then ever are familiar with the methods of mental prayer once associated with contemplatives and consecrated religious. On another level, though, are we modern Catholics merely dabblers, building a spirituality like a magpie constructs a nest, selecting bits of the tradition out of the past like we might select breakfast cereals from a supermarket aisle?

I was once one of those dabblers. When I first became serious about following Christ, I found the cornucopia of liturgical expressions, prayer methods, and even translations of the Bible dizzying. I sampled many flavors of the faith, from Ignatian contemplation to the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite to a Life in the Spirit seminar. Eventually I calmed down. Eventually, too, I found my humble little home in the Church by developing a friendship with a monk from Portsmouth Abbey in Rhode Island and pursuing a vocation as a Benedictine oblate. I have since moved to northern Virginia, and transferred my oblate formation to Saint Anselm Abbey in Washington, DC, a sister abbey to the one in Rhode Island.

As you might know, praying with Scripture is one of the foundational practices of the Rule of Saint Benedict. In monasteries and convents in which the Rule is followed to the letter, the monks or nuns practice Lectio Divina for at least two hours a day—three during Lent. Now, as a married lay school teacher, I do not have the hours in my day to even attempt this. Like other oblates, I adapt the Rule to my particular circumstances so that I might join my prayer to the prayer of the monks. Lectio Divina has become one of the pillars of my rule of life, albeit in an abbreviated form.

Perhaps this is a good time to mention that there are dozens of ways nowadays to pray “Lectio Divina”. To some, Lectio Divina is having well curated discussion questions to ponder after reading a chapter of scripture aloud in a group. To others, it is simply a name for applying the text to ones current situation. These are certainly valid and useful, but represent something entirely different from the method practiced by the ancients and medievals.

My own practice of this method has been particularly formed by two books, one video series, and one monk. The books in question are Praying the Word by Enzo Bianchi and The Ladder of Monks by Guigo II. Both are in print as part of the Cistercian Studies series. The former is a wonderful contemporary book written by the founder of an ecumenical monastery in Italy. The latter is a text from one of the early Carthusians which is the most complete explanation of Lectio Divina as practiced by Medieval monastics. Besides these two books, the works of Michael Casey, OCSO are also excellent. Both Sacred Reading and Toward God contain practical advice on the practice of prayerful reading in the ancient tradition as well. Perhaps the clearest and most succinct treatment I have seen on the subject, though, is a conference on Lectio Divina by Father Cassian Folsom, OSB that is freely available on Youtube. You will not regret sitting down for a half hour and listening to this.

Like learning to pray the Liturgy of the Hours, a real live human sitting at a table with you is probably still the best way to learn Lectio Divina. I hope that this blog post is a bit like my sitting in your computer room with you, our Bibles on our laps. For me, that person was Brother Sixtus at Portsmouth Abbey. One afternoon two summers ago we sat together at the monastery and he answered my questions on prayer. I have found these conversations with monks decisive in my life. I ask all who read this to pray for vocations to the American monasteries of the English Benedictine Congregation.

What Bible do I use?

Well, I use this one.

In a way it is funny to me that this Bible has been a big part of my life the last few years, and I don’t think I have ever mentioned it on this blog. My writing on the blog, and its predecessor, has been on bespoke topics and not on anything so personal as how I pray after dinner. I suppose I started submitting articles only because I could find nothing online to answer the questions I sought to answer: Which edition of the NAB is closest to the American Lectionary? How much does the Lectionary revise its NAB source material? How different is the NABRE Psalter from the Revised Grail Psalms? Was Eugene Peterson at all inspired by the Knox Bible? Is there a point in owning both the Ignatius Study New Testament and the Navarre Bible New Testament? What the heck is going on with David Bentley Hart’s translation? Why does the CSV exist? (Some of these questions are indeed unanswerable.)

My personal Bible reading migrated from the NAB to the RSV around 2018 as a result of using more study helps that were keyed to that translation in particular. In 2021, however, Brother Sixtus suggested I try praying with the New Jerusalem Bible. I had a salty disposition toward the whole Jerusalem Bible family that I had to get over. I had bought a copy of the Jerusalem Bible after my reversion experience. I had heard of its literary qualities and its links to Tolkien. I was more than a bit baffled to find none of the style and poetry I expected. It seemed to fall in between two stools for me. It did not seem to be as useful for study as the RSV or NAB, but nor did it have the great beauty of the Knox, NEB, or REB. I unloaded it on a friend soon after. Suspiciously, I followed the monk’s advice. In the rectory I was working in at the time, there was an old copy of the NJB. I took it off the shelf.

So what was the reason to make the NJB my Lectio Divina companion? Was it the Benedictine connection? Henry Wansbrough OSB, the one man revising team for both the NJB and the RNJB, is a monk of Ampleforth Abbey, one of the largest monasteries of the English Benedictine Congregation—the same line of the Benedictine family tree as the two abbeys I have connections to. As much as I am proud to call myself a vocational third cousin, twice removed, from this esteemed biblical scholar, that is not it. No, it is the pages themselves of the NJB’s study edition which are so helpful. It is an incredibly well annotated Bible. Its notes are scholarly and give us the fruit of historical critical study without soiling the page with an atmosphere of arid skepticism. This Bible also has the best cross reference system of any Catholic Bible I have ever used.

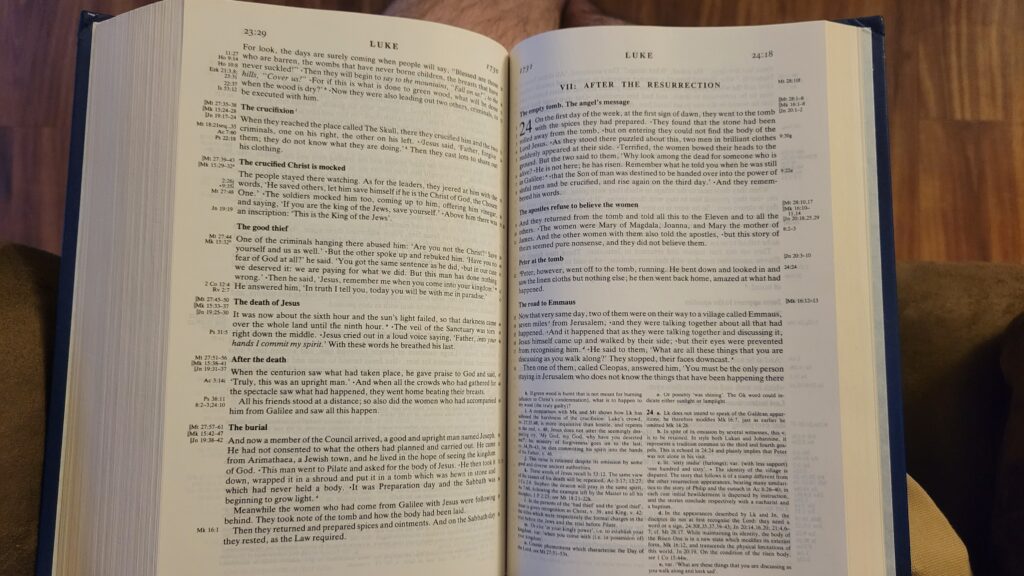

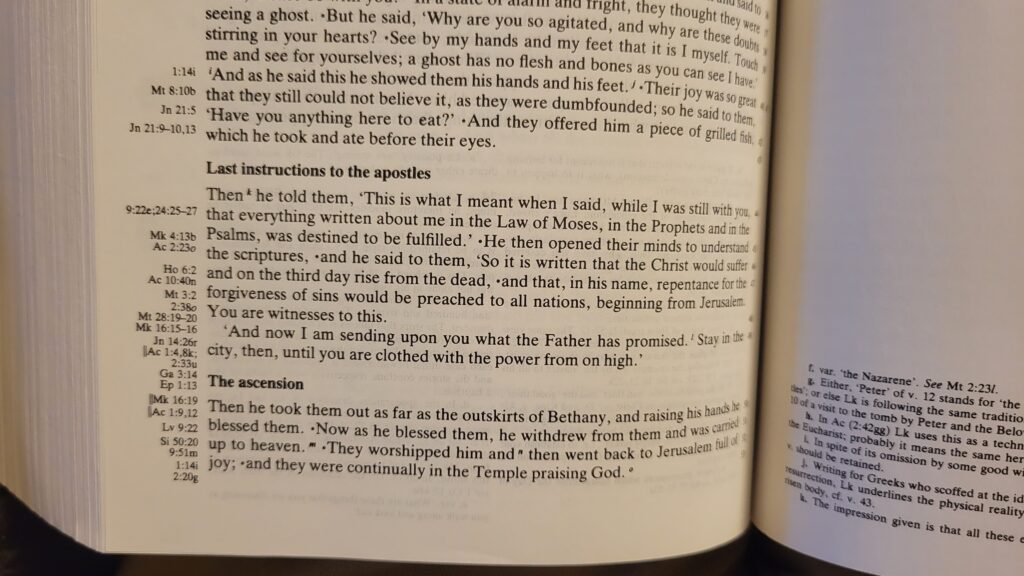

As you can see, the page is single column, with a heaping portion of cross references in the margin. You will see later how I use cross references in my prayer. Let’s take a closer look at the supplementary material associated with the telling of the Ascension from Luke’s Gospel. Whereas the Ignatius Bible simply points us to two parallels in the book of Acts, and the NABRE adds to these the mention of the Ascension in Mark’s longer ending, the NJB does much more.

As a word of explanation, the double line next to the first two cross references to the left of the words “The ascension” are used to show parallel passages. Notice that above and beyond what the NABRE and Ignatius Bible had, the NJB points us to Leviticus 9:22 (“Aaron then raised his hands towards the people and blessed them. Having thus performed the sacrifice for sin, the burnt offering and the communion sacrifice, he came down.”) and Sirach 50:20 (“Then he would come down and raise his hands over the whole assembly of the Israelites, to give them the Lord’s blessing from his lips, being privileged to pronounce his name”). Both references are to the priesthood of Aaron, that which Christ fulfills and supersedes. Now, keep in mind that for the full effect, the cross reference is not simply pointing to the exact verse, but to the entire setting and context of these verses. They also point us to footnotes associated with Luke 9:51, 1:14, and 2:20.

As an important caveat, these features are only found in the study edition of the NJB, not the various reader editions. The study edition has been out of print for a while now, but can still be found easily on the secondary market. The study edition of the Revised New Jerusalem Bible has much the same format, but the binding, the notes, and the cross references are a definitive step down from the NJB. Keep in mind that the RNJB was mainly a rather successful attempt to update the NJB translation and make it more literal. It was not an attempt to update the study bible as such. I would like some confirmation on this, but I think the notes and cross references of the RNJB are directly carried over from Wansbrough’s annotations to the CTS Bible project, which was a UK edition of the original Jerusalem Bible to match what was in the Lectionary (“Lord” rather than “Yahweh”, and the Grail Psalter instead of the JB book of Psalms).

Which Scripture do I pray with?

Now let us get down to brass tacks. You are in your prayer chair. Your bible is on your lap. What section will you pray with?

There are two errors we should avoid. The first is to flip to any page whatsoever and assume that it is God who has selected the passage. Yes, sometimes the Spirit will be protecting you from your own nonsense and give you something good, but more likely than not you will be dipping in and out of biblical books somewhere between 2 Samuel and Jeremiah at random and spending way too much time having to orient yourself within the literal sense of a randomly selected text rather than going ever deeper in the spiritual sense of the text of a book you have been progressing through. The equal and opposite error is to follow our own feelings and only pray with familiar and well loved passages. We can’t pray about the Gospel pericope of the good Samaritan, prodigal sun, or the road to Emmaus forever. The scriptures are a big library, and every word has something to offer us.

The two best methods are praying along with the Mass readings or working through a Biblical book continuously. I do a combination of the two. During Christmas, Lent, and Easter I pray with the Gospel of the day. During most of Advent I focus on the Old Testament reading. During Ordinary Time, I work through books of the Bible. I have been very slowly working my way through Matthew. If I live long enough to complete the Gospels, I suppose I will switch to the letters of Saint Paul, or Isaiah, or the Song of Songs.

What are the steps?

Lectio: Reading

Having chosen a chunk of text of a chapter or less, I sit down with my Bible. It is unfortunately easy for my eyes to scan a page as if reading without me paying any attention whatsoever. It is harder to do that if I read aloud. I first read the passage quietly aloud to myself about two times. Then, I educate myself on the passage. I ask myself if anything confuses me about the passage. I read the NJB’s annotations. Often if I am unsatisfied I will consult the Ignatius Study Bible New Testament, or a Navarre Bible commentary. I am also a big proponent of the Ancient Christian Commentary series by IVP. It is the RSV text with commentary from the Fathers, ending with Bede the Venerable. Eerdman’s has or had a similar series called “The Church’s Bible”, of which I have the volume on the Song of Songs. The cool part of that series is that it goes through the commentators of the Middle Ages as well. You will have your favorite resources. Use those. Having a general understanding of the literal content of this piece of scripture, we go deeper. Before I meditate, however, I read the passage out loud again once or twice in order to re-enter the world of the Bible and leave the world of commentaries behind.

Meditatio-Meditation

One thing to get clear right off the bat is that what we think of as “meditation” nowadays is influenced by translations of Buddhist and Hindu spiritual works and not the Christian use of the term. What I once thought of as “meditation” is actually “contemplation” and what I thought of as “contemplation” is actually “meditation”. A helpful image to go with is a cow chewing its cud. You are chewing on the Word. Just as ruminants (even toed ungulates with multiple stomachs) ruminate their tough but nourishing food by sending it back up to the mouth before swallowing it again, we must chew on the Word and experience its sweetness. Practically, I choose a verse or part of a verse that I want to live with for a day or so. I read it and repeat it a number of times. I have some index cards I cut in half near my prayer chair. I will write the scripture I have ruminated on in pencil on one of these cards and carry it around with me for a day until I pray with scripture again. At times during the day, I will take it out of my pocket and read it to myself. Historically, a focus of this step in Lectio Divina was to memorize the scripture. Select significant verses that you would like to memorize. You will not always commit one of these to memory, but they will certainly become places in the Bible you have a personal relationship with.

Oratio-Prayer

There is an excellent example of this stage of Lectio Divina in the conference by Fr. Cassian Folsom OSB mentioned above. In it he runs through some examples of how one would pray with the gospel of the two disciples encountering the risen Christ on the road to Emmaus. This part of the prayer is intensely personal. It will be different for each of us. For me, I read through the text slowly one more time. At the end of each verse I pause, and speak a prayer to God in reaction to what I have read. Soon I will submit to Marc a follow-up to this article in which I run through an example of Lectio Divina with a particular Gospel passage. Some keep their prayers formal, almost like the Collect of the Mass. Others are rather chatty with the Lord. You know what will feel right for you.

Contemplatio-Contemplation

And now I close my eyes. In this stage, I have spoken and am giving the Lord a chance to answer. I finish with 10 minutes or so of focused, attentive silent, thoughtless, and imageless prayer. Of course, I try for this to be focused and attentive. Anyone who prays in this way knows that you will be bombarded by thoughts. Do not entertain the thoughts. Wait for the Lord.

How long does this whole process take? It depends chiefly on how long the passage of Scripture is, how much time we spend in meditatio and how much time we spend in contemplatio. I usually budget 25 minutes for this prayer. You can imagine how long the steps could be stretched out for a monk who has two to three hours set aside for this task. We are not monks, however, and can joyfully give the Lord what we have. He will not turn us away but will send us home with nourishing food for the journey.

Thank you! Very informative and helpful. I am very drawn to lectio divina but I am a real know-nothing about the Bible: I only started going to church in my thirties (I’m 41 now) and my general level of familiarity with the Scriptures is therefore very low. For now I’m trying to approach the Bible the way a newcomer to Tolkien would approach TLOTR and the Silmarillion, reading through it as a narrative and trying to get the lie of the land. Then I hope (!) lectio divina will work better as the next step after that. If anyone thinks I’m going the wrong way about it I’d be interested to hear.

My conversion experience was in my mid 20s. It took me years to figure out my prayer life and really get a sense of scripture. One resource I think would be worth checking out would be the one coauthored by Tim Gray and Jeff Cavins. Is it called Walking with God? It has a very nondescript title, but is very, very good. There are similar books by people like Edward Sri too. Once I got the flow of the biblical history, the literal sense was easier to understand and it was easier to simply pray with scripture rather than study it. An edition of the Bible that also helps in this is the Great Adventure Bible. It has the RSV.

I will pray for you as you continue to grow in your relationship with God and the scriptures!

I always appreciate the Jerusalem Bible tradition living on. I view it in a special class, finally a break from that Tyndale sound we have in the RSV line. Personally, I have no interest in the RNJB because I think its notes are decidedly a step down from its predecessors, not to mention binding and the typos and things like that, and even at its most “literal,” it’s still comparatively dynamic to the other options out there. However, I nevertheless appreciate my 1966 “New Testament of the Jerusalem Bible” hardback, because it has all the original notes but isn’t the famously bulky full Bible that you could bash someone’s head in with. I pondered trying to find a NJB version of that NT-only hardback if it exists, but at the end of the day I thought, if I was going to experience the Jerusalem Bible in all its dynamic equivalence glory, and experience the translation that was used for so many decades in so many English Masses, I had to get the original. Not my devotional or study translation, but definitely a pleasant reader from time to time.

This is a wonderful article and I thank the author for writing and for it being shared.

I do have a general question to everyone. There was a comment in the article about the dissatisfaction with the JB and the RJB hit the sweet spot for the author.

I have the JB and love it and I’m curious about how the RJB is perhaps superior to the JB. I’ve mentioned this interest is not for those with OCD tendencies so now I must have opinions!

God bless all who read this.

Peace

Sorry I meant NJB not RJB in my query

This is only subjective, but for me the JB is dynamic without being particularly beautiful–neither as starkly beautiful as the Tyndale line, nor as literary as the Knox or the NEB (which I think is extremely underrated in its literary style). When I read it, I feel like my attention has nothing to grip onto. Now, I realize the changes between the JB and NJB are comparatively minor, but for me, in a very subjective way, they make all the difference. I find myself enjoying the read quite a bit.

As for the RNJB, yes it is a shoddier piece of work in terms of the book itself, but I think its a worthy successor for a slightly different audience. Its notes are no longer meant for deep study, but for the same kind of imagined audience the NAB notes were for. Even being more literal, it is still rated as less literal than any edition of the NAB, never mind the RSV and ESV.

If I was a theologian or an apologist, an extremely literal translation would matter very much to me. I am neither a theologian nor an apologist, Deo gratias.

Thank you!

Love this!

It would appear that this particular NJB study edition is a gem because quite a few websites are selling it in the $50-$80 range.