After an endless series of articles talking about the philosophical basis (or is it bias?) of David Bentley Hart’s translation, and his singular perspective, it is time to get into the nuts and bolts of what readers experience when they open his translation. After some quick notes about the text he translated and some physical features of the book itself, we will go straight to some verse examples. If I missed one you find very important for your enjoyment of a translation, let me know in the comments and I will try to help you, within reason.

Textual Basis

Hart writes about the text he translated for almost three pages at the end of his introduction. He translates the Critical Text, using a variety of printed editions from the Wescott and Hort text of 1881 all the way to the current UBS and Nestle-Aland editions. He also puts Majority Text readings in the text in brackets. He lists several printed editions of the Majority Text that he referenced, but notes that he considered the Greek Orthodox Patriarchal Text of 1904 to be normative. So, John 5:4 and the woman caught in adultery is in the text, but in brackets, the ending to Mark is present in brackets but set off from the rest of the text, while the Johannine Comma is not present at all, as it is neither in the Critical Text nor the Majority Text.

Some details about the physical book and design:

–It is a sewn hardcover that lays flat between the middle of Mark and the start of Hebrews. Perhaps my copy could be broken in more, but I generally don’t abuse the spines of books.

-It is the size of a new hardcover novel with thick paper which is fairly opaque.

-It is neither extraordinarily heavy or light for its size. I don’t find it comfortable to read with one hand.

-The text is paragraphed with unobtrusive verse numbers and chapter divisions in a gray type face.

-There is nothing set as poetry, not even the canticles from Luke and the epistles.

-Each new verse begins with a capital letter, whether it is the start of a sentence or not. I have gotten used to this, but still wish it were not so. This is, to me, the worst design feature of this New Testament.

-The text is large, bold, and easy to read. (R. Grant Jones estimates the size as 11 point.)

-Footnotes are in a smaller, but still quite large font. (R. Grant Jones estimates them as 9.5 point.)

-I find it easy to go from the text reference to the footnote, but find doing the reverse very difficult. Eventually I highlighted the footnote references in the text as an aid for my reading.

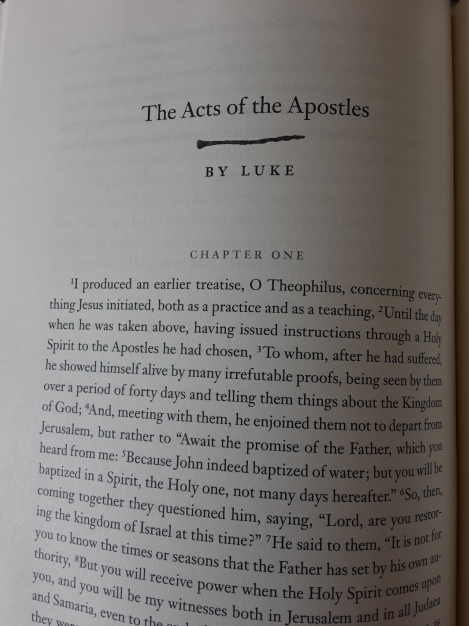

-There are no section headings and the top of the page does not clue you in on where in the text you are, which sometimes can slow you down if you are hunting for a specific verse. To illustrate this, I opened up my copy randomly just now, and was able to tell I was somewhere in the middle of Acts of the Apostles, but was unable to recognize what chapter I was in without turning back or forward. How much of a problem is this really? Not a large one. This is not the sort of New Testament that people are going to be doing “sword drills” with.

-There are no book introductions, and each book of the New Testament begins with its title, which is separated from the text (or in some cases, as the picture below) by the image of a nail.

A hearty sample of favorite verses

Note that I have not transcribed verse numbers, footnotes, or capitals at the start of verses in most of these examples.

Matthew 2:1-2

“Now, Jesus having been born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days when Herod was king, look: Magians arrived in Jerusalem from Eastern parts, saying, “Where is the newborn King of the Judaeans? For we saw his star at its rising, and came to make obeisance to him.”

I thought Magians was an odd choice, and was surprised to see that Richard Lattimore also uses this rendering. It must be a Classicist thing.

Matthew 3:13-15

“Then Jesus arrives at the Jordan, coming from Galilee to John to be baptized by him. But he prevented him, saying, ‘I need to be baptized by you, yet you come to me?’ But in reply Jesus said to him, ‘Let me pass now; for it is necessary for us to fulfill every right requirement.’ Then he lets him pass.”

Matthew 5:3-12

“How blissful the destitute, abject in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens; how blissful those who mourn, for they shall be aided; how blissful the gentle, for they shall inherit the earth; how blissful those who hunger and thirst for what is right, for they shall feast; how blissful the merciful, for they shall receive mercy; how blissful the pure in heart, for they shall see God; how blissful the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God; how blissful those who have been persecuted for the sake of what is right, for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens; how blissful you when they reproach you, and persecute you and falsely accuse you of every evil for my sake: rejoice and be glad, for your reward in the heavens is great; for thus they persecuted the prophets before you.”

Matthew 6:9-13

“Therefore, pray in this way: ‘Our Father, who are in the heavens, let your name be held holy; let your kingdom come; let your will come to pass, as in heaven so also upon earth; give to us today bread for the day ahead; and excuse us our debts, just as we have excused our debtors; and do not bring us to trial, but rescue us from him who is wicked. [For yours is the Kingdom and the power and the glory unto the ages.]”

Matthew 11:28-30

“Come to me, all who toil and are burdened, and I shall give you rest. Take my yoke upon yourselves and learn from me, because I am gentle and accommodating in heart, and you will find rest for your souls; for my yoke is mild and my burden light.”

Matthew 28:19-20

“Go, therefore, instruct all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe everything that I have commanded you; and see: I am with you every day until the consummation of the age.”

Footnote from Mark 16:9-20

“The final twelve verses of the Gospel are set apart here because they are a somewhat later addition, absent from the text known to the earliest Church Fathers. Whether they were added to compensate for the abruptness of Mark’s conclusion (intentional or accidental) or to replace a lost original ending (which is not unlikely, given the hazards afflicting the transcription and preservation of manuscripts in late antiquity) we cannot say. That they were not written by Mark, however, is beyond serious doubt.”

This pericope is treated differently from all other sections of text, even interpolations. It is bracketed, but also set off from the rest of Mark by the same image of a nail that can be found under the title of this book—something not even done for the episode of the woman caught in adultery.

Luke 1:28-34

“And going in to her he said, ‘Hail, favored one, the Lord is with you.’ And she was greatly distressed at his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be. And the angel said to her, ‘Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. And see: You will conceive in your womb and will bear a son and you shall declare his name to be Jesus. This man will be great and will be called Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob throughout the ages, and of his kingdom there will be no end.’ And Mary said to the angel, ‘How shall this be, as I have intimacy with no man?’

Luke 1:38

“See: the slave of the Lord; may it happen to me as you have said.” And the angel departed from her.”

“See” or “look” for the Greek word traditionally rendered as “behold” is one of those things that bothers me, even if I know it shouldn’t. In this translation, though, I don’t mind it as much, because it is so plainly non-liturgical. “Behold” would probably seem out of place here.

Luke 1:46-55

“And Mary said, “My soul proclaims the Lord’s greatness, and my spirit rejoices in God my savior, because he looked upon the low estate of his slave. For see: Henceforth all generations will bless me; because the Mighty One has done great things to me. And holy is his name, and his mercy is for generations and generations to those who fear him. He has worked power with his arm, he has scattered those who are arrogant in the thoughts of their hearts; he has pulled dynasts down from thrones and exalted the humble, he has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty. He has given aid to Israel his servant, remembering his mercy, just as he promised to our fathers, to Abraham and to his seed throughout the age.”

Luke 1:68-79

“Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, because he has visited his people and bought their liberation, and raised a horn of salvation for us in the house of David his servant—as he said through the mouth of his holy prophets of old—salvation out of the hands of our enemies and out of the hand of all who hate us, to work mercy with our fathers and to remember his holy covenant, the oath he swore to Abraham our father, to grant that we, having been delivered without fear from our enemies’ hands, might worship him, in holiness and justice before his presence for all our days. And now you, little child, will be called a prophet of the Most High; for you go forth before the presence of the Lord to prepare his ways, to give his people a knowledge of salvation in the forgiveness of their sins, through our God’s inmost mercy whereby a dawning from on high will visit us, to shine upon those sitting in darkness and death’s shadow, so to guide our feet into the path of peace.”

Luke 2:29-32

“Now you release your slave in peace, Master, in keeping with your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have made ready before the face of all peoples, a light for a revelation to the gentiles and a glory for your people Israel.”

These show one limit of this attitude of “make it as literal as possible so the modern reader can experience what the first century reader did.” Well, the first century reader would have experienced these passages as poetry. The literary quality of these renderings is not bad, but they don’t strike me as poetry. I wonder, though, how much of that is that they are set as prose. Are our minds really so suggestible? I think they are.

Luke 16:9

“And I tell you, make friends for yourselves from the Mammon of unrighteousness, so that when it gives out they may welcome you into the tents of the age.”

Note: “Aeonian. Perhaps, however, here meaning only ‘enduring a long time,’ or ‘lasting through this age,’ or ‘enduring for life.’ This is an instance where the settled habit of translating aionios—here in the plural form, modifying ‘tents,’ (tas aionious skenas)—simply as ‘eternal’ or ‘everlasting’ except in cases where it absolutely cannot have that meaning, serves to veil an ambiguity of the text. It is traditional to read these words eschatologically, as referring to ‘everlasting abodes’ (or some other ethereal phrase that somewhat dissembles the rather homely image of ‘tents’), and this may well be correct. But it is not at all clear that, at this point in the text, Jesus has taken leave of the ‘earthly level’ of imagery, and he may be speaking literally of shelters in this world that will last a lifetime (one of the possible acceptations of aionios).

More on this aeonian business next episode.

Luke 16:16

“Until John, there were the law and the prophets; since then the good tidings of God’s Kingdom are being proclaimed, and everyone is being forced into it.”

Note: “Biazetai: While it is traditional to translate this verse as saying that ‘everyone forces his way into’ the Kingdom, the verb biazomai much more typically has a passive force. In fact, this is true of its every other instance in either the New Testament or the Septuagint. The tendency to treat it here as active is almost certainly an attempt to bring it into conformity with the imagery (though not the syntax) of Matthew 11:11-12; yet, curiously enough, even there the same verb carries a passive force, only with ‘Kingdom’ rather than ‘everyone’ constituting its subject. It seems clearly better, then, to read this verse in continuity with 14:21-23 above (and perhaps as an analogue of John 12:32).”

Luke 18:25-26

“‘For it is easier for a camel to enter the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the Kingdom of God.’ And those hearing this said, ‘Can any of them then be saved?’”

Note: “The text speaks of a kamelos, acc. kamelon, ‘camel’, but from the early centuries it has been an open question whether it should really be the homophonous (but poorly attested) word kamilos, ‘rope,’ ‘hawser’: a more symmetrical but less piquant analogy. Kai tis dynatai sothenai: often translated as ‘who then can be saved? or ‘can anyone then be saved?’ but I take the import (specifically as regards the tis) to be ‘Can any [rich man] then be saved?”

John 1:1

“In the origin there was the Logos, and the Logos was present with GOD, and the Logos was god”

You don’t get the full effect without seeing this on the page. In a long note, Hart writes of how depending on the capitalization, you can tell whether John is writing of God with the definite article (“which clearly means God in the fullest and most unequivocal sense”), God without the definite article and other forms of the Greek word. This is all building up to the scene where Thomas says “My Lord and My God”, and for the first time in the Gospel someone has called Jesus “O Theos”, God in the fullest sense.

John 2:4

“And Jesus says to her, ‘what madam, is this to me and you? My hour is not yet arrived.”

Note: “gyne: ‘woman’ (as distinct from ‘maiden,’ ‘virgin’), ‘wife’. As denoting a married woman and mother rather than an unmarried girl or maidservant, it is a perfectly polite term of respect, a fact that is somewhat obscured in traditional translations that render its vocative use here simply and curtly as ‘woman’.

John 3:3

“In reply Jesus said to him, ‘Amen, amen, I tell you, unless someone is born from above, he cannot see the Kingdom of God”

John 3:16

“For God so loved the cosmos as to give the Son, the only one, so that everyone having faith in him might not perish, but have the life of the Age.”

John 7:53-8:11

Much like in John 2:4, Hart takes great pains in a note to point out that Jesus is “neither dismissive nor condescending” in calling the woman caught in adultery “woman” (“madam” in Hart’s translation). In a subsequent note he details the reasons scholars think this episode was not written by John and was not originally located there. However, he goes on to write, “this does not mean, however, that the episode is some late invention inserted into the text to make Jesus appear more compassionate…For one thing, in late antiquity—Jewish, Christian, or pagan—it would have been far more scandalous than commendable in most eyes for Jesus to have allowed an adulteress to go away not only unpunished, but entirely without rebuke. For another, there is good reason to think the episode may in fact be drawn from an older narrative source than the Gospel itself: there is a tale of a very sinful woman that the early second-century Christian Papias mentioned as being part of the lost Gospel of the Hebrews; the Syrian Didascalia (from the third century) cites ‘the story of the adulteress’; the Constitutions of the Apostles (in a portion probably also from the third century) relates a similar story of a sinful woman whom Jesus refused to condemn; and both Didymus the Blind and Jerome mention the tale as appearing in many manuscripts before the end of the fourth century. Moreover, the earliest texts of John do not merely lack the story; in its place are diacritical marks indicating that something (maybe the same story, maybe something else) has been omitted. Augustine, in fact, aware of the story’s absence from many texts of the Gospel, opined that perhaps it had been removed because the offense it might give to pious souls unable to understand how Christ could excuse so grave a transgression with no more than an exhortation to sin no more. It seems the story was something of a freely floating tradition, perhaps with very deep roots in Christian memory, one that was not originally firmly associated with any particular Gospel text, but that was inserted in various versions of Luke or John because it was too beautiful and too illuminating of Christ’s ministry and person to be left out of the church’s lectionary cycle (and hence out of scripture).”

John 8:58

“Jesus said to them, “Amen, amen, I tell you, before Abraham came to be, I AM.”

Acts 7:53

Note: “…The phrase is strange, and interpretation is complicated by the reality that, in late antique Judaism, it was common to understand all of God’s dealings with creation as conducted not immediately, but only through angels who seemingly enjoyed a certain autonomy or defectibility in regard to how they discharged their missions, and who perhaps delivered the Law to Israel in a form proportional to their own limited powers. Thus for Paul, in Galatians 3:19-20, the Law ‘having been ordained by angels’, ‘in the hand of an intermediary [Moses],’ is holy but still inferior to God’s direct promises. And in Hebrews 2:2-4 the Law merely spoken through angels is not yet equal to, or as final as, the word spoken directly by the Lord.”

Acts 10:13

“And a voice came to him: ‘Arise, Peter, sacrifice and eat.’”

A note defends the rendering versus the commonly used “kill”.

Romans 9:5

“Theirs the fathers, and from them—according to the flesh—the Anointed; blessed unto the ages the God over all things, amen.”

Note: “A verse whose syntax and uncertain punctuation make it liable to a variety of interpretations. It can be read, as it is here, as if the ‘Anointed’ comes at the end of a sentence or clause, followed by a doxology. Or it could be read: ‘the Anointed, who is God over all things, blessed unto the ages, amen.’ Or (though less plausibly), ‘the Anointed, over all things; blessed be God unto the ages, amen.’…Theological tradition favors the first of these alternate renderings; but though Paul in Philippians speaks of Christ’s equality with God, and though Christ’s divinity is obviously indubitable for him, he nowhere else speaks of Christ simply as o theos, ‘God’ specified by the definite article, which it seems likely was for him (as for most of his contemporaries) a privileged name for the Father. Moreover, the concluding ‘amen’ seems to indicate a doxological, not a predicative, formulation.”

1 Corinthians 1:20-24

“Where is the wise man? Where the scribe? Where the dialectician of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the cosmos? For since in God’s wisdom, the cosmos did not know God by wisdom, God thought it well to save the faithful by the foolishness of a proclamation. Since Judaeans ask for signs while Greeks seek wisdom, and we proclaim the crucified Anointed One—both a stumbling-block to the Judaeans and a folly to the gentiles, but to those who are called, Judaeans and Greeks alike, the Anointed One, God’s power and God’s wisdom.”

1 Corinthians 11:5

“But every wife who has her head uncovered when she is praying or prophesying shames her head; for it is one and the same thing as its being shaven.”

Note: “…There have been many elaborate discussions of these verses (4-16), but both the issue and the energy with which Paul addresses it may be easily understood if one recall that he belonged to a culture of extreme modesty, in which a woman’s full and lustrous head of hair was regarded as among the chief beauties of her sex; hence, a woman’s uncovered head in public, and especially in places of worship, was seen both as an ostentation and as an ill-mannered provocation (rather as, today, immodest dress is discouraged in many places of worship).”

The full note itself is half a page long and concludes with the rather simple and illuminating conclusion that while with men their head covering itself was a sign of style and status, for women it was a sign of modesty. Thus, for each sex to humble themselves before God, one was to take off their head covering and one was to keep it on.

1 Corinthians 11:10

“Therefore a woman ought to keep ward upon her head on account of the angels.”

The note on this verse takes up 16 lines of text. I mainly cited this verse because I found it amusing that the note began with the words, “No one knows what this verse means.”

1 Corinthians 23-29

“For from the Lord I received what I also delivered to you: that the Lord Jesus, on the night in which he was betrayed, took a loaf of bread, and having given thanks, broke it and said, ‘This is my body, which is [being broken] for your sake; do this for my remembrance.’ Likewise after supping, the cup also, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this as often as you drink, for my remembrance.’ For as often as you eat the loaf and drink the cup, you announce the Lord’s death until he come.”

1 Corinthians 14:34-35

“[Let the women in the assemblies be silent, for it is not entrusted to them to speak; rather let them be subordinate, as the Law also says. But, if they want to learn anything, let them inquire of their own husbands at home, for it is an unseemly thing for a woman to speak in an assembly.]”

Note: “These verses are a considerable textual problem, as they clearly constitute an interpolation that breaks the flow of the text, and that seems written in a voice unlike Paul’s, and that contradicts other passages in Paul. Simply on its face, the argument reads coherently only when these verses are removed…From a broader perspective, moreover, it is absolutely clear from the discussion on women’s head-coverings in chapter eleven above, and particularly at 11:5, that Paul fully expects women to speak and prophesy in church, and clearly approves of the practice so long as women do not provocatively flaunt their ‘glorious’ hair while doing so. And, in fact, the whole tenor of Paul’s genuine writings is one of almost unprecedented egalitarianism with regard to the sexes (Galatians 3:28 being perhaps the most famous instance, but 7:4 above being no less extraordinary for its time).”

This note is over 2/3rds of a page in length and goes on into the specifics of manuscripts and critical editions from the first six Christian centuries that treated this passage as a possible interpolation. He concludes by saying, “In any event, the best critical scholarship regards these verses as a later and rather maladroit interpolation, perhaps drawn from 1 Timothy 2:11-12; and the evidence preponderantly indicates that they are almost certainly spurious.”

2 Corinthians 6:1-2

“And, cooperating with him, we also implore you not to receive God’s grace in vain; for he says, ‘In an acceptable time I heard you, and on a day of salvation I helped you.’ Look: Now is an acceptable time. Look: Now is a day of salvation.”

Note: “Synergountes: ‘coworking,’ ‘acting with’; here, in keeping with Paul’s characteristic language of the ‘synergy’ of divine and human works, the word should be read in continuity with the final verses of the previous chapter, where Paul speaks as God’s ambassador, through whom God implores the Corinthians to be reconciled with him. Hence, Paul and his companions are synergountes with God, not merely ‘fellow workers’ with the Corinthian church.”

Galatians 4:3-7

“So also we, when we were infants, were enslaved in subjection to the Elementals of the cosmos; but when the fullness of time had come God sent forth his Son, coming to be from a woman, coming under the Law, so that he might redeem those under the Law, in order that we should receive filial adoption. And, since you are sons, God sent forth his Son’s Spirit into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba!’—Father! Thus you are no longer a slave, but a son; and, if a son, also an heir through God.”

Note: In a long note Hart recounts possible ways of understanding what he renders as “the Elementals”. These could be the malicious spirits of the universe, idols, the flesh, or even the introductory lessons of the world, to fit in with the pedagogical theme in parts of Galatians.

Ephesians 1:3-14

I’m not going to transcribe all of this—even if it one of the most breathtakingly beautiful sections of scripture, even in a literal translation like Hart’s—but I want to point out that in Hart’s rendering it is all one sentence. Here are the stats on some other translations:

Douay-Challoner: 5 sentences

ESV: 5 sentences

RSV: 6 sentences

NABRE: 5 sentences

NRSV: 6 sentences

NIV: 5 sentences

NT Wright: 14 sentences (!)

Assorted book titles:

The Letter to the Romans-By Paul

The First Letter to the Corinthians-By Paul

The Second Letter to the Corinthians-By Paul

The Letter to the Galatians-By Paul

The Letter to the Ephesians-Attributed to Paul

The Letter to the Colossians-Attributed to Paul

The First Letter to the Thessalonikans-By Paul

The Second Letter to the Thessalonikans-Attributed to Paul

The Pastorals are also listed as “Attributed to Paul”, Philemon to Paul, and Hebrews to “Author Unknown”. The Letter of James appears without attribution, while both letters of Peter appear under “Author Unknown.” The First Letter of John is labeled as: “Attributed to John the Elder”, whereas the other two letters of John are simply “by John the Elder”. What we usually refer to as the Letter of Jude is known here as the Letter of Judas (the names are apparently identical in the Greek) and Revelation is attributed to “John the Divine of Patmos”.

While moving the doubt about traditional explanations of authorship from the small italicized print of an introduction to the very title of a book would strike some as a new level of Historical-Critical aggression, Hart is himself dubious of some of the arguments of the critics. We will get into this in the next episode, but Hart writes that he felt more open to the fact that Paul had (in some way) “written” Ephesians and Colossians after having translated the New Testament than he had before. His comments on authorship in his “Concluding Scientific Postscript” (as he calls it) are quite interesting.

Hebrews 1:1-2

“God, having of old spoken to the fathers by the prophets, in many places and in many ways, at the end of these days spoke to us in a Son, whom he appointed heir to all things, and through whom he made the ages:”

The colon is not a typo—that is how Hart punctuates the end of that verse, but I didn’t want to transcribe any further here.

Hebrews 11:1

“Now faithfulness is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of unseen realities.”

Revelation 12:1-2

“And a great sign was seen in heaven: a woman garbed with the sun, and the moon beneath her feet, and on her head a chaplet of twelve stars, and she was pregnant, and she cries out, enduring birth-pangs and in an agony to give birth.”

Revelation 13:1-3

Note: “Though Revelation is written in the coded language of apocalyptic literature, and many of its more recondite references are irrevocably lost to the past, on the whole its symbolism is not difficult to penetrate. It is concerned principally with the Roman Empire, the city of Rome itself, the emperors of Rome, and Jerusalem—both its destruction and its future divine restoration—as well as the final vindication of believers in Jesus as the Messiah…”

What follows is an in depth analysis of the seven emperors of Revelation, and the eschatological significance of Nero in the imagination of the eastern empire in the years after his death. A later note discusses the reasons scholars think the “number of the beast” is a code of his name.

Revelation 21:1

“And I saw a new sky and a new earth, for the first sky and the first earth have passed away, and the sea no longer is. And I saw the holy city, a New Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God, made ready like a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘Look: The tabernacle of God is with human beings and he will tabernacle with them, and they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them [as their God], and he will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and no longer will there be death, no longer will there be sorrow or lamentation or pain, for the first things have passed away’.”

I also found Hart’s translation of Matthew 5:27-28 to be unusual and surprising. It goes along with some of the other verses you highlighted, Bob, where Hart makes distinctions between the Greek words for a married woman versus a maiden:

“‘You have heard it said, “You shall not commit adultery.” Whereas I tell you that everyone looking at a married woman in order to lust after her has already committed adultery with her in his heart.”

Hart’s note is also interesting: “(gyne): ‘woman’ (as distinct from ‘maiden,’ ‘virgin’), ‘wife.’ Here the topic is clearly a man who wishes to violate the marriage covenant of another man’s wife.”

Hart’s distinction is not merely in the Greek word’s as they translate mechanically, but in what Jesus is saying. Matthew 5:27–28 looks to be a reference to the Ten Commandments, namely Exodus 20:17, against a man coveting his neighbor’s wife. It was not seen as wrong to desire another “unmarried” woman and thus commit adultery against one’s wife.

It should be noted that the words of Jesus themselves are extraordinary in that unlike the Mosaic Law, which seems to only condemn women with the ability to commit adultery, Jesus here states that men are the main (and in the gender that it is written, only) culprits.

There was a ritual in the Mosaic Law in Numbers chapter 5 that was to be used to tell if a woman was suspected of being guilty of adultery, but the Law had no such avenue for men. Wives could not, under the Mosaic Law, bring their husbands before the Eternal One, and ask for the Ritual to be performed in an accusation against them.

But in the New Covenant preached by Jesus from in the Sermon on the Mount, women are not addressed by the Messiah when it comes to adultery. The imbalance is “taken care of,” so to speak. (While it does apply to women, symbolically only males are addressed.) Men are said by Jesus to be only the ones engaging in secret adultery by looking at women in public and dreaming up in their hearts scenarios how they will use them for their own selfish gratification.

In Numbers chapter 5, the act of dealing with a suspected adultress publically shamed a woman likely for life, whether she was guilty or innocent. To have undergone such a public ordeal must have left a mark not unlike the famous Scarlet Letter.

Masterfully, Jesus turns things around, using the word “adultery” as a term that seemingly only “men” can commit. In this, he brings about a symbolic fulfillment of Hosea 4:14 where God promises to throw out accusations of adultery against women and turn attention now to the adulterous act of men, even though the Mosaic Law gave no precedent for such. Jesus’ speech is egalitarian and forceful.

That may be what Hart’s note says, but that doesn’t make sense in the context, and it defies 2000 years of Christian interpretive tradition. If the question is ‘who is wrong, Hart, or everyone else?’ the question isn’t difficult for me to answer.

Even Jewish scholars, on reading that passage, agree that Jesus is expanding the prohibition against adultery to include fornication and lust. In fact, what Jewish scholars such as Jacob Neusner have noted is that Jesus is following a traditional rabbinic principle called ‘building a wall around the Torah’ in which they say that not only is one required to obey the 10 Commandments, but one is required even to avoid situations which may lead to one feeling tempted to violate a commandment. So, to avoid failure to fulfill an oath, never make an oath at all, to avoid murder, avoid even situations that may make you feel angry enough to commit murder etc. Catholics would call this ‘avoiding the near occassion of sin’.

My first thought is that Hart’s translation and note on these verses isn’t opposed to the point you raised, BC. To my mind, his interpretation of this is still in keeping with the idea of “building a wall around Torah.” The argument would be that anyone who desires to break a married woman’s marriage covenant is already guilty of the act itself. This is very much in keeping with the overall point in the passage: look to the heart, not simply the outward actions.

The late Jacob Neusner’s work has been put to critical examination, and it has been found that he did not have a good knowledge of ancient Hebrew, and was especially ignorant of its rabbinical use during the Second Temple era, the period in which Jesus lived. The claims Neusner made during his lifetime about that period were found to be unreliable.

See Solomon Zeitlin, “Spurious Interpretations of Rabbinic Sources in the Studies of the Pharisees and Pharisaism,” Jewish Quarterly Review, 62, 1974, p. 122-135; John C. Poirier, “Jacob Neusner, the Mishnah and Ventriloquism,” The Jewish Quarterly Review, LXXXVII Nos.1-2, July–October 1996, p. 61-78; Hyam Maccoby, “Jacob Neusner’s Mishnah,” Midstream, 30/5 May 1984 p. 24-32; Shaye J. D. Cohen, “Jacob Neusner, Mishnah and Counter-Rabbinics,” Conservative Judaism, Vol.37(1) Fall 1983 p. 48-63.

I was not aware of these criticisms of Neusner’s work. A few months ago, I purchased “Judaism When Christianity Began” (by Neusner) to learn more about the Jewish context that Jesus was immersed in. Are there other books that you would recommend for understanding first century Judaism?

A single-volume approach is impossible in my view. Yet the following should work together:

“An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus” by Lester L. Grabbe

“The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words, 1000BCE – 1492CE” by Sir Simon Schama (You may also want to watch the PBS docu-series “The Story of the Jews” which is hosted by Schama, available sometimes on Amazon Prime too.)

“The Jewish Annotated New Testament: Second Edition”–Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, Editors

“The Misunderstood Jew: The Church and the Scandal of the Jewish Jesus” by Amy-Jill Levine

The New Testament itself grants much insight into the Second Temple era. The problem for the Christian is that they forget to read it as Jewish literature. It is often read as Christian-not-a-product-of-Judaism literature. That is why I highly recommend the last two books. When one remembers that the first Christians did not see themselves as disconnected from Judaism (the non-Gentile Christians still practiced it), then one can learn to use the New Testament as a means to see into the Second Temple era better than using most any other Jewish writings of the same period.

Thanks Carl! I’ve ordered the Jewish Annotated New Testament, and I’ve added The Misunderstood Jew to my list. These look like excellent resources.

Carl,

As Marc did so did I. These books open a whole new world of learning, perspective, and knowledge in what I thought was familiar territory, i.e., the New Testament.

In your commentary on Matthew 2:1-2 I think that should read ‘Richmond Lattimore’.

Yes you are certainly right! Oh my goodness, I own a book by him and have mentally gotten his first name wrong every single time I have thought it!